News | Long Beach Community Data Walk- Not Your Average Walk in the Park

Stop the VideoNews

Long Beach Community Data Walk- Not Your Average Walk in the Park

Thursday, September 30, 2021

CSULB researchers engaged a group of Long Beach-based volunteers in applied community research with a data walk on July 1st. The data walk is part of a larger Pacific Southwest Region (PSR)-funded research project, “Using Artificial Intelligence to Improve Traffic Flows, with Consideration of Data Privacy Principles,” to install and evaluate smart traffic light controllers that could potentially reduce freight truck-induced traffic delays. The first phase of this project includes surveying residents about their privacy concerns regarding the installation of new technology, and is led by Dr. Gwen Shaffer, CSULB Associate Professor in the Department of Journalism and Public Relations, and Dr. Tyler Reeb, CITT Director of Research and Workforce Development. CSULB Engineering Professor Anastasios Chassiakos and CSULB Engineering Lecturer Dr. Hossein Jula will lead the second part of the project involving the collection and analysis of data from traffic light controllers.

Data Walk 2021

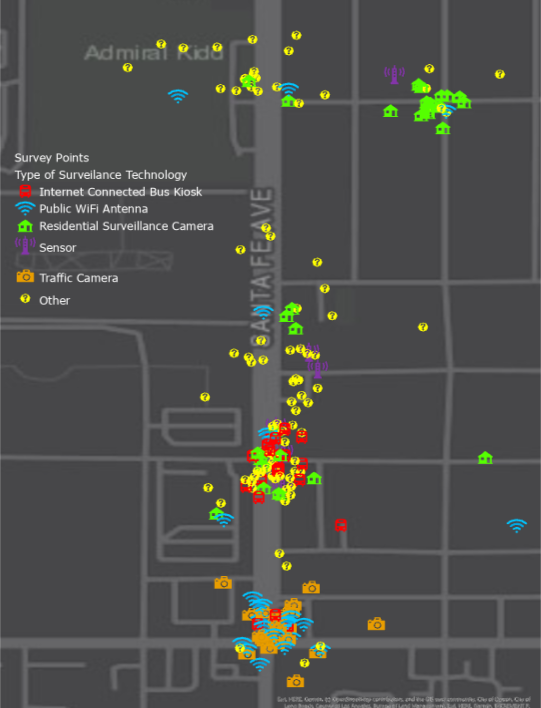

To stimulate conversation in Long Beach about data collection and the trade-offs that accompany the implementation of smart city technologies, Shaffer designed and facilitated the data walk for multiple groups of participants. Reeb and CITT Communications Manager Natalie Reyes helped coordinate and promote the walk to Long Beach residents in order to garner community participation. Participants documented and discussed the smart city technologies (e.g. public Wi-Fi networks and license plate readers) observed throughout the pre-designated route, which covered a blend of residential and high-traffic commercial streets that included a West Long Beach neighborhood, a four-way business intersection, a police station, and a city park. CITT Research and GIS Coordinator Ben Olson and Research Assistant Adam Doyle created an interactive questionnaire survey and map for the participants to use as they traveled the route.

The map shows points along the route where participants logged a device

As devices were pointed out along the walk, participants were asked to take a photograph, log the technology in the interactive survey, and record their prior awareness of the smart technology. The facilitator then informed them of any tracking or surveillance properties associated with the technology. Participants were asked to give their perspectives on whether the surveillance and data tracking was something that made daily life more convenient and created a feeling of increased safety, or if they felt that it was excessive and presented privacy concerns. During three separate walks, a total of 32 volunteers (all Long Beach residents) participated in the 1.5-mile walk—learning about emerging technology in ways beyond the surface, with discussions of smart city ethics, privacy, data collection, and potential convenience and security advantages.

Some smart technologies included in the walk, discussion, and questionnaire survey were the traffic cameras at intersections, internet-connected bus kiosks and sensors, data and passwords that are retrieved by using publicly available Wi-Fi networks, and the varied data collection from commercial and residential surveillance cameras. Most of the participants said they realized surveillance and security cameras existed, but that most had not noticed the number of cameras around prior to the data walk. The combined presence of these smart technologies means some form of data is collected for any individual walking or driving along a route, although access to that stored information varied according to the ownership of the device or network. When encountering a traffic camera owned by the Long Beach Department of Public Works, one participant typed into the app that their acceptance level “depends” on why the camera is collecting personal data. “If I ran a red light, yes. Any other time, no.” Another study participant acknowledged daily trade-offs with technology: “It’s a little uncomfortable but, I think, worth the compromise.” These comments highlight the importance of community involvement and discussion about the deployment of smart city technologies.

There are practical benefits to the implementation of smart technologies, including increased connectivity and security. With internet-connected bus kiosks and applications, for example, riders can easily check schedules and stay updated in real-time on bus delays or changes. Combining smart technologies and transportation can help reduce accidents and increase safety. The devices can also help address issues like traffic and congestion by gathering data on problem areas and facilitating deeper, more informed research and solutions. Cities have numerous reasons to consider implementing smart technologies as solutions; but, as demonstrated by Shaffer’s data walk, the foundational step in designing smart city programs is involving the community and assessing residents’ comfort level with data collection and surveillance. “The study found that attitudes toward smart technologies varied depending on context—for example, whether the technology is intended to protect property versus to inform targeted ads,” Shaffer said. “Comfort levels also fluctuated based on how transparent officials and businesses were about how they stored and used residents’ data.”

News Archive

- December (1)

- November (6)

- October (4)

- September (2)

- August (3)

- July (4)

- June (3)

- May (7)

- April (8)

- March (11)

- February (8)

- January (7)

- December (7)

- November (8)

- October (11)

- September (11)

- August (4)

- July (10)

- June (9)

- May (2)

- April (12)

- March (8)

- February (7)

- January (11)

- December (11)

- November (5)

- October (16)

- September (7)

- August (5)

- July (13)

- June (5)

- May (5)

- April (7)

- March (5)

- February (3)

- January (4)

- December (4)

- November (5)

- October (5)

- September (4)

- August (4)

- July (6)

- June (8)

- May (4)

- April (6)

- March (6)

- February (7)

- January (7)

- December (8)

- November (8)

- October (8)

- September (15)

- August (5)

- July (6)

- June (7)

- May (5)

- April (8)

- March (7)

- February (10)

- January (12)